A sensible approach to compensation for remote teams

Feb 23, 2023

I've recently joined a new startup with some old friends. Matt (the founder & CEO) and I were on the same page about so many things when we started talking about potentially working together again. Having seen the inside of a number of companies over the past decade it was interesting how to see how similar our lists of "this approach is broken" and "this works well" were when it comes to building and growing a company.

So while Ockam is in an interesting problem space, that already has an impressive community and traction, and it's exciting to be back in the deep end at an early stage company again there's another small reason I joined. One that people don't talk openly about very often: Compensation. In particular, Ockam's general approach to it.

But before we get to that let's have that open talk about how compensation is usually approached. Because unless you've been on both sides of the table there's a good chance you've not thought through the incentive structures of all the parties involved or the cascading affects of decisions.

Real-talk about how your employer approaches compensation

Every company I've ever worked at that's large enough to have a dedicated team (even if it's only a single person) that's responsible for compensation planning has taken basically the same approach. If you're at a company with more than a few hundred people then it's highly likely this applies to you whether you realise it not (unless you're in a sales role. People with commission structures should ignore everything I say).

Let's start with what might seem obvious, what is "compensation"? It's what you get paid. Duh! Your compensation is then typically a mix of your base compensation, probably an equity grant, possibly a sort-of-guaranteed regular bonus, maybe a hiring bonus. Let's call the aggregate of all of these your "total compensation".

This is where the specifics can vary wildly between companies, and even between roles within a single company. The ratio between each of those components is going to be very different. How much each increases during a promotion cycle will be different. Whether they treat them as indendent dials to turn for specific individuals, whether they bias towards one for certain types of incentive/retention, or whether they look at the aggregate and try and keep the total in a specific band. All that's important for the sake of this essay is that the general shape of how things are done will be pretty similar across most companies. They'll just vary which parts of your compensation they apply this approach to.

There's only so much to go around

The inescapable truth is that at any point in time your company has only got so much they can afford to pay people. They've either raised investment, and the more they pay people the shorter their runway will be. They've taken on debt and the more they draw down on it the higher the interest costs are and the more they ultimately have to repay. They're paying out of cashflow, often slightly more than is coming, with the expectation that spending it now means more will come in later and it's all worthwhile. Or there's profits in the bank and you're drawing down on them, meaning you can't spend them on other things. These might also seem like very large numbers! Even so, it's finite. Everyone has a budget they have to work within.

Balancing "fairness" with compensation efficiency

Time to be blunt: compensation is entirely a commercial transaction. Your company might talk about it in terms of paying you fairly, individuals (especially in smaller companies) might genuinely believe that. It's not what actually happens in the aggregate though. Paying you "fairly" is about paying you enough to reduce the probability you'll leave. Compensation efficiency is a more serious way of saying "pay them as little as possible".

Sounds horrible when you say it like that, right? We should unpack why it's not people being as horrible as that makes it seem. Remember that budget people have? For the sake of simplicity lets keep the numbers nice and round: there's an additional $100K in the budget to spend on compensation over the next year. There's currently a team of 10 people, all earning $100K. How do you spend the $100K? As that team's direct manager you probably want to do right by your team. They've been doing great work, you want to keep them, inflation is super high at the moment, they all deserve a 10% pay rise. You give them all the pay rise, that's the whole budget gone. But you know there's only going to be more work to get done next year. Does giving everyone a pay rise also mean they're suddenly going to be able to find a way to get 10% more done too? We've already acknowledged they're performing well, there's probably not a whole lot more we could reasonably ask from them. So how does the additional work get done? If we didn't give anybody a pay rise we could use that $100K to hire another person onto the team. That'd help get the work done. Not an immediately great story for the morale of the current team though, they'll be bummed. That'll probably incur a productivity hit. More than the hit we take burning people out asking them to somehow squeeze more work into their day? Hard to say, it might net out. Will people be so dissatisfied about the lack of pay rise they leave? Maybe. More than those that would leave from the burnout case? Who knows with these hypotheticals, maybe it's the same outcome? It's pretty easy to come to the conclusion that the better outcome here is more people, which means paying less. The company is also spreading their risk/bus factor if they do that. The incentive here is to make the money go as far as possible.

Hey, I never promised I could make this sound appealing to you! It's not great thinking you're on the receiving end of this. But this is the #realtalk section. The "company's" interests are in ensuring the company survives as long as possible. It's not about paying you as much as you think you deserve. Those two things are usually at odds with each other. The sooner you accept that it's all just business and nothing personal the better. Ironically, realising it's not personal should make it easier to advocate for your own interests. The pushback you receive isn't necessarily about you specifically, so don't take it to heart. You absolutely should still maximise for getting paid what you feel you're worth as soon as possible, but we'll get to that later.

Paying people too little has its consequences. The company will find it more difficult to attract the type of people it wants to hire. It will struggle to keep the people it already has if they're getting more competitive offers from other companies. It may have a negative impact on motivation and productivity will take a hit as a result. If someone leaves, there's a significant impact to the business. The obvious reduction in output from having one less person, all the time and energy and focus diverted from many others to hire a replacement, the lag between the person leaving and a replacement both joining and then being ramped up and able to contribute. All of these are very negative impacts to a company. So they'll want to minimise them as much as possible. One way (out of many) to minimise the probability of these situations occuring is to pay people more.

But let's be clear: your employer is incentivised to push as close to the line on this as possible. Not because they're jerks, just because it's the most efficient thing to do.

The promotion & review cycle

At least once a year, for some companies two or three, there's the promo & review cycle. You'll do the dance of making your case for why you deserve a promotion to a new more senior level, or maybe just a pay rise. Maybe you'll have to build a case with support from some peers. There will be a 360 feedback process. Maybe there's a system where "stakeholders from across the business" will be asked to provide feedback to direct your manager, which they'll aggregate and share any themes that emerge. Done well, all this can be quite beneficial at helping you grow and become more effective.

It's got basically nothing to do with your compensation though.

"Whaaattt?! But it's the promo cycle time! That's the time the company works out pay rises! They've told us that! You're wrong."

I've got news for you: if you're getting promoted to a new level it's got nothing to do with the documentation you spent two weeks writing to make your case. Or the half dozen paragraphs of supporting text collected from a handful of peers. It's the year or two of work preceeding all of that. The paperwork is to make your bosses' case easier to support a decision that is already made. Though it wont necessarily be clear to your boss either in that moment what exactly that decision is.

Because months prior a bunch of accountants would have run the numbers and come up with... a budget. Remember we spoke about one of those earlier? There's one here too. How it gets applied will vary from company to company, based on market conditions, and again may be applied either to individual aspects of compensation or to the total compensation amount. I'll again make up some figures, but based on my experience they'll be within a realistic range. Each business area will be given a total budget, and typically some guidance on how it should be deployed. Labels like "high priority retention", "at level", "low urgency", and "non-regrettable attrition" will get thrown around. Basically clinical ways to discuss the spectrum of "people we want to keep" to "no big loss if they leave". The guidance will then be something like 8% compensation increase for "high priority retention", 4% for people performing "at level", and possibly nothing for anything below that.

Then the reviews and calibrations begin. Someone, somewhere, is going to grade everyone on a curve. Maybe it's not your manager, it might be their manager, maybe it's the head of finance or the CEO. But I can assure you there's not going to be a situation where all the management submissions come back, everyone is graded as "high priority retention, please give them an 8% pay rise", and the company turns around and thinks "oh, we incorrectly budgeted this. We're going to have to pay everyone a lot more than we expected". Implicit in the budgeting decisions was a model with some kind of Guassian distribution of pay rises. How many promos and pay rises could be given out was decided long ago. Way before the performance appraisals came in. By a bunch accountants. Remember it's not personal, just business.

Pay scales and indexing

You may have encountered pay scales before, in various jurisdictions or sectors they've had to be made public. Other times companies talk about them under the guise of being transparent and ensuring fairness. How true that is really depends on how they're deployed.

I'll start with the positive implementations. In many public sector roles there are very strict and narrow bands for compensation, that are publicly available and usually published with a job posting. You know upfront either the exact amount you'll get paid or a tight range it will sit within. No or little negotiation possible. No or little risk of bias in the process re-inforcing systematic discrimination.

Most companies, even at their most bureaucratic, can't match the public sector for that level of inflexibility though. So the pay scales exist mostly as a starting point, or worst case as a justification for why they're unfortunately unable to adjust compensation to meet your expectations. When a job gets posted an expected level will get assigned, that'll initially get used to help calibrate screening for suitable candidates. Then you'll spend weeks or months interviewing people. Finally you get to the offer stage, but the candidate decides to negotiate hard. The compensation they're asking for is outside the range originally assigned for the role, and you're confident they'll walk from the current offer. Does the company let them walk and have a half dozen people spend more months trying to find someone else? Of course not. They come back with an offer that will be accepted. Either by offering above the range or through title/level inflation (i.e., giving someone a more senior role than their experience would suggest their equipped for, just to keep them in official comp ranges).

So how exactly are the ranges for each level determined? There will usually be some third party involved. A company, analyst firm, or similar that generates reports on salaries. The company will target a certain percentile amongst a group of "peer" companies. Let's say "70th percentile". That means they're aiming to be in the top 30% of companies in terms of compensation. It all gives a good air of impartiality and independence. "We're not just making up these numbers, we're just using a third party firm and then making sure we're near the top". Not at the very top though. It's about finding that balance where they can pay enough to attract people while simultaneously paying as little as possible. There can be a lot hidden in the finer details on the definition of "peer companies" too though. What constitutes a peer company? Are specific companies being excluded? Are you tracking base salary or total comp? I've seen two basic modes of operating here: very generic and simple or customised. Generic and simple is usually because it's quicker and cheaper to just have a basic framework and have everyone get back to work. If it's customised it's because there's real economic value to the company for being able to tweak the definitions to find the most favourable interpretation of the numbers. Lies, damn lies, and statistics.

The geography overlay

Just for an extra bit of fun, companies will usually throw a geographic adjustment to the pay bands or actually index each role to the pay ranges the research firms report in each local market. Again there's a pretty bimodal approach to this in my experience: simple or sophisticated.

The sophisticated approach is to get real granular. Individual states, maybe even individual cities in some places. Pay based on what the local market pays for that particular role. The rationale will often be something like "we can't skew the local market, we need to be in line with peer companies within a region". I get the impression people who've told me that line genuinely believed it themselves, I think some people are just especially comfortable swallowing the company line uncritically. It's nonsense. Tech salaries in Seattle are as high as they are because Microsoft and Amazon are there. Companies have absolutely no problem skewing the local market when they think it's in their interests to do so. This has never been about some noble desire to slow the roll of gentrification and late stage capitalism in our suburbs.

No, it's about the same efficiency everything else here has been about. So if a "Senior Engineer in Seattle" earns $200K/year and a "Senior Engineer in Vancouver" earns $150K/yr the company will pay $50K/yr less for the person in Vancouver. Hey, it makes good business sense. Nothing personal. If you can get the same job done by someone who is $50K/yr cheaper just because they live 150mi further north you'd take that deal too.

I find a far more insidious aspect of this though that the super fine-grained resolution, applied over the top of anything from 5 to 12 levels, across multiple functional areas, manager and individual contributor tracks... it makes any pretense that it's about fairness and consistency disingenous. When you've got >3000 individual "salary ranges" there's plenty of places to find whatever justification you want.

Individual maximisation

Ok, this might all seem a bit grim. It was meant to be a bit of an exposé of how many companies handle compensation because not enough people have seen the inside of the process. And while I've painted a picture of a system that isn't optimising for the individual and where decisions that impact you are made far away from your influence. Don't dispair! It might not optimise for the indivual but you absolutely still should. So before we wrap up this way too long setting of context and move into talking about what Ockam did different that caught my attention, let's talk about individual maximisation. Let me introduce Sarah, she's a composite character of actual circumstances and events I've witnessed as part of hiring and compensation planning teams over the past 15 years...

Sarah is a very talented engineer. She's managed become very accomplised with a very niche technology, but one that's become critically important to handful of companies that are doing very sophisticated things in this new "cloud" thing. She's interviewing at a few companies in the Bay Area and gets offers from all of them. Very good offers! But there's one in particular she really wants to work for, an exciting startup, but unfortunately it's the lowest of the offers. She's transparent about that and says the disparity is just too much. The startup is desperate though, there's just not many people with this expertise in the market right now. They decide that despite only having a couple of years experience they'll hire her as a "Senior Engineer" to get her offer in line with what she's looking for. Success! Everyone is happy and gets to work.

Within a year the startup is acquired. Not really long enough for Sarah to have vested much equity, but she's loving her work so she's not bothered by that. And the acquirer is pretty hands-off apart from standardising on some of the HR and similar processes. One of those standardisation aspects is the approach to compensation and promotions. Despite coming in more senior than she probably should have she's doing a great job. Maybe still not quite at what they'd typically hire as a senior, but far too good to risk losing. So in the promo cycle her manager flagged her as "high priority retention" and the good news is it's boom times and the parent company had a great year so there's a tiny bit more to go around than usual so she gets a 10% pay rise.

She's growing weary of San Francisco though, most of her team is spread across North America anyway (the startup had a largely distributed team from the start). She decides she's moving to Great Falls in Montana. She makes sure her boss is cool with it, he is, but he mentions that the new owner of the company indexes to the local market. There's not really a local market for what she does in Montana though and so when her manager speaks to HR about it they inform him it'll be a $100K/yr pay reduction to her. He passes on the bad news. Sarah informs him the pay cut isn't going to happen because she's going to be just as productive working with her remote team from there as she is from San Francisco. He agrees, and they decide to just not talk to HR about it again. She moves and keeps her salary.

Next promo cycle comes around and suddenly people realise that Sarah's address and comp band don't line up. When they adjust her to the Montana salary ranges she's wwwaaaayyyy off the charts. There's an emergency meeting with Sarah, her manager, and the compensation team to try and reset her expectations. "We're terribly sorry, but you're going to have to be ready for a significant reduction in your compensation. Or you'll have to reconsider moving back to San Francisco". Unfortunately for the compensation team they're outmatched by someone who has grown in both confidence and competency over the past 2-3 years with the company, "If I move back to San Francisco, I'll keep my current compensation?". "Correct". "Thanks, I just wanted to be clear that this has absolutely nothing to do with what you're willing to pay me. You seem to be under the impression that there is some market for people with my skills in Montana, and that you could hire my replacement from that pool. If there is you should absolutely hire those people immediately. There is not. Not only is there not a pool of these people in Montana, there's no pool of them globally. There's about 6 people in the world who know how to use this technology to this level, and the other 5 are already on my team. If I quit you're either stuck with a team of 5, or you have to hire me back". Well played, Sarah. The double-edged sword of giving so much back to the open source community is you can rapidly accelerate someone's development to the point that they're now a core contributor to some of the most critical software your company is running on. Compensation teams hate this 1 weird trick!

Not only does Sarah keep her current salary, not only is she once again "high priority retain", but she's been growing in confidence and influence. Lots of really, really positive growth. She's definitely performing at the top end of senior now but she's been here almost 3 years at the same level and so her manager had steeled himself to push for her promo. A confluence of fortunate events happen for Sarah: there's been a whole lot of attrition recently. Lots of the early employees have left in recent months given they're fully vested, which has meant both lots of backfill alongside all of the growth hiring. That means there's a lot of employees who've been at the company less than a year and so aren't eligible for promo. Her boss had built a pretty compelling case for the promo and thought the areas where she excelled would hopefully hide the gaps that still exist. He probably didn't need to bother though. There's so few people up for promo that it went through unchallenged. The system doesn't know how to deal with individuals, it just expects a certain percentage of people to go through the process. She made it through.

For the comp ratios to work again HR have had to do something in the backend to keep her on the Bay Area salary bands. And now she got a promotion to "Staff Engineer". She didn't just keep her salary, she came away with another 10% pay rise! As well as a very generous stock refresh.

Every time compensation is discussed manangers and HR go to great lengths to explain to Sarah how out of band her compensation is. "We index to the 70th percentile in the local market, and your current compensation is way above that. I need to stress how little flexibility we have in terms of any future compensation increases". It's a story she's heard dozens of times. It really ramps up around promo season. But she continues to do exceptional work. She continues to get flagged as someone they can't afford to lose. And so she continues to get the "high priority retain" compensation increase each year. Because the system doesn't know how to discriminate.

Fin. (Of Sarah's story)

This is obviously a golden tale about a high performer. If you're performing and in-demand though it's in your interests to maximise the things you can influence. Because maximising those means that when the system works in your favour the effect is amplified. Think about the compound interest on all those decisions and events. Influencing the initial negotiation to get the higher comp (and level), the system them amplifying that in the promo cycle, holding strong on the regional adjustment, system amplifying, etc.

For many tech workers the difference can literally be hundreds of thousands of dollars over just a few years. A delta that only grows over time.

Whenever, wherever, and however you can make sure you get paid.

Ockam's compensation approach

Whew! That was a lot.

After all of that this is probably going to be pretty boring because of the simplicity, and in my opinion, the sensibility of it all. As a hiring manager I found the huge disparity between salary bands in different regions infuriating. It made no sense that I'd have to consider giving someone in a low compensation market an inflated title just to get them what they asked for. Meanwhile we'd have another candidate in the pipeline who was more junior but would be paid more, even on a lower title, than the first candidate because they were in a high compensation market. But big companies need complicated systems.

Then there's the various aspects of Sarah's story where it becomes obvious that there's "the rules" and then there's reality. And the rules only apply to some people. Turns out that almost all of them are negotiable for the right people. The definition of "right people" is in part people who are in high demand and have leverage, but more than anything it actually meant "people who knew they could negotiate an exception for themselves".

So when Matt & I finally sat down to discuss compensation at Ockam he said "I think you'll like this", and he was right. It felt like we'd observed the same anti-patterns and special exceptions and he'd decided to both simplify it and make those exceptions apply to everyone so they weren't exceptions any more:

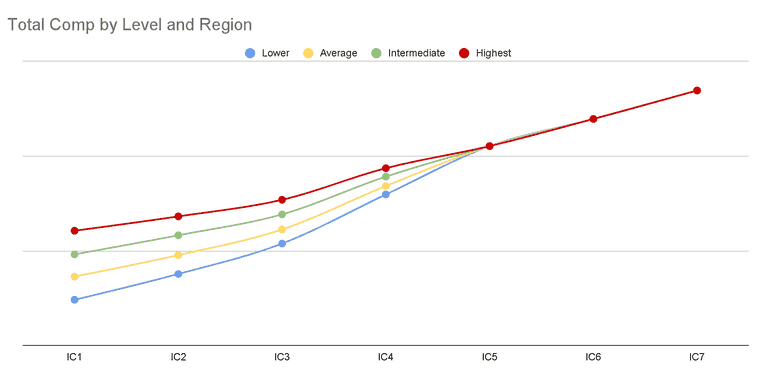

For a start they index at 75th percentile, so far pretty standard. But the index is only of private SF/SV from the Carta benchmark report, a simple approach that skews toward the top end of actual peers rather than being creative. Localization, but a completely tractable one. It's not over 50 discrete states, it's 4 global regions grouped roughly by cost of living. Discount slightly from the SF/SV salary based on the reduced cost of living in other locations. No local market for a Rust engineer in Montana? No problem, the base rate is taken from the SF rate anyway.

How much do you discount though? Well it varies by level. The most junior role has the most discount applied (it still isn't much), and as you become more senior the gap closes. Anyone at the IC5 level or above is being paid at the SF/SV rate. And... I think it just made sense? It's what I'd seen play out time and time again from people who knew they could negotiate. Especially amongst those that accepted a role in SF and then later decided to move and refused to take a pay cut with it.

Which brings me to another aspect of Sarah's story, the need to maximise negotiation outcomes. From the Ockam handbook: "We aim to have consistency in our compensation across the entire team and remove negotiation bias. Since we are a global company, there are different social norms and expectations for negotiating an offer to join a company. We remove this bias so that as we grow we don't end up with different compensations for different categories of people.". I've seen the long-term implications of people who didn't negotiate well enough on the way in. It's almost impossible to fix. The compounding impact means that the gap between two genuine peers who negotiated differently ends up only growing wider over time. In reality the only way it gets fixed is the person leaves and gets the compensation they should have been getting at a new company.

Especially given so many companies over the last few years have moved to having distributed teams I'm disappointed so few of them have been proactive in taking a global approach to compensation. I get it though, why bother? If you can keep a complicated system that keeps costs low then why would you change it? Different companies have different priorities though. So I greatly appreciated the fact that Ockam's priorities were around simplification and just getting straight to work. The time and energy we'd spend collectively micro-optimising this stuff is time and energy wasted. It's obviously a point of difference too. A potential marketing and recruitment tool for people who want to see companies take a new approach to thinking about compensation. It worked on me! 😉

The Team Handbook that covers all of this is publicly availble. I've linked straight to the compensation section, but it's worth reading the whole thing.

Previously I led the Terraform product team @ HashiCorp, where we launched Terraform Cloud and set the stage for a successful IPO. Prior to that I was part of the Startup Team @ AWS, and earlier still an early employee @ Heroku. I've also invested in a couple of dozen early stage startups.